A response to some recent criticism of “popularism”

On the difference between campaigns and "movement building"

Two weeks ago, a new substack called Loop Me In – run by an anonymous crew of progressive political staffers – started up.

The authors are planning to focus on questions about Democratic party tactics, something that I spend a lot of time thinking about in my work at Blue Rose Research, and have written about a fair amount. From what I’ve read so far on the site, the Loop Me In authors seem smart, and seem to be writing in good faith. I subscribed, and if you’re interested in this sort of thing, I recommend you do too.

I want to respond to two pieces they’ve put up, on “The Anti-Politics Of Popularism,” and “What Democratic Disagreements on Tactics Obscure.” I’m not mentioned by name in the pieces, but in their posts, the authors have cited a few different articles I wrote, so I feel at least somewhat invested.

What they’re saying:

The pieces are linked above, and this article will probably make the most sense if you read them first (they’re fairly short). But here’s a quick summary if you’d rather not do that.

The authors correctly describe “popularism” as consisting of, roughly, the ideas that:

Current electoral trends (rising educational polarization, declining ticket splitting) will result in a dire situation for the Democratic party, especially in the Senate.

This would be very bad, especially due to the risks of democratic backsliding.

To avoid it, we should try to appeal to the non-college educated voters who (due to our biased electoral system) tend to decide elections

Appeals to these voters are, in general, best done by increasing the Democratic party’s emphasis on economic issues (relative to social issues), and having the party advocate for more popular stances on both sets of issues

So far so good. This is certainly what I – a “popularist,” I suppose, though I’m not a huge fan of the label – think.

The authors then write the following:

What Democrats need more of is movement building. The best hope for reversing the societal decay driving Americans to retreat into a permanent anti-social defensive crouch, is building and strengthening organizations that can politically mobilize people to (as one big fan of movement building put it) fight for someone they don’t know.

And that:

Previous generations have attempted this hard work of political persuasion and succeeded, and they did it largely by engaging in what popularists disdain most: extra-electoral activism and organizing designed to change public opinion and convince those with power to deliver on new policies. As Sam Adler Bell argues, the labor movement, “a movement of the left that mobilizes and draws us together on the basis of our most basic associations and material interests,” is the best place to start.

Here’s what’s funny to me about this: while the piece these quotes are pulled from is explicitly framed as a critique of the writing and the work of folks like me and my friend David Shor, I actually found myself nodding my head along to much of it. This shouldn’t be particularly surprising to anyone who is familiar with my actual politics. I did, after all, support Bernie Sanders in the 2020 Democratic primary. I’ve also been a strong supporter of organized labor for as long as I’ve been interested in politics, and I would love to see unions pull the Democratic party back to its materialist roots.

I agree with the following, as well:

Politics isn’t easy! We aren’t trying to win elections to stay in power – we’re trying to improve people’s lives. Polling and analytics are tools in that fight – but if something that is normatively good is unpopular, it’s on us to change voters’ minds.

We should, of course, try to change people’s minds. That is a key part of politics, and has been for as long as politics has existed.

However.

Once we accept that changing minds about policies is crucial, the question remains, when, how, and in what context should we try to move public opinion? I think my disagreement with the authors at Loop Me In – if such a disagreement exists – boils down to a disagreement on the nature of “movement building” vs “campaigning.”

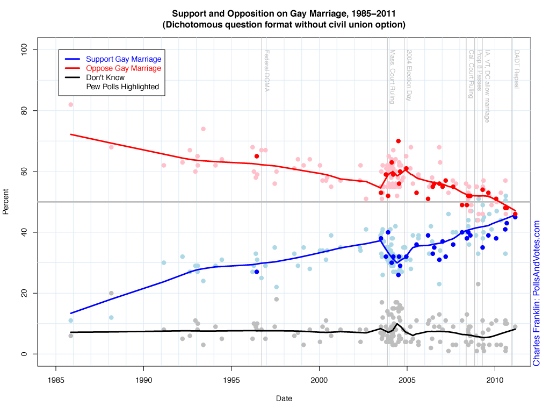

I tend to think that political campaigns are a terrible place to try to durably and significantly change public opinion on the issues. Campaigns are short, high stakes, and highly contentious, Even an issue that’s gaining steam can be derailed by entering the center of the political arena. One example of this is marriage equality. Look at the chart below of public support for gay marriage being legal. The blue line – support – has a steady upward trend, except for one year: 2004. Not coincidentally, that’s the year that gay marriage was most salient in a presidential election. Marriage equality becoming a major part of the political conversation didn’t move hearts and minds in the progressive direction; what actually happened was that Republican partisanship was activated and the issue temporarily lost ground.

Yes, mass public opinion is influenced to some degree by what politicians say on the campaign trail. But in the long run, it’s much more heavily determined by elite discourse in both the media and in popular culture. The people who change views in the long run are folks like opinion writers, and television host, but also and especially cultural elites, like filmmakers, singers, and novelists. Critically, it’s this latter group that I think is best positioned to make cultural change.

Perhaps a pithy way of summarizing my point here is to say that Hollywood producers putting more gay characters in TV shows likely did far more to spread acceptance of the LGBT community than the Democratic party embracing gay marriage did. If you’re trying to change hearts and minds – a worthy goal, to be clear – you should probably go work in pop culture instead of politics. (A great example of someone who did this in a way that I really respect is Ta-Nehisi Coates, who ditched Twitter and The Atlantic, and moved over to comics instead, becoming the author of Marvel’s Black Panther.)

But this kind of cultural change is slow. In general, it’s probably too slow to affect the results of the next election. Given that reality, candidates and political operatives still need to pick their messaging and ideological positioning with an eye toward the current state of public opinion. With a real risk of authoritarianism in play, that ought to mean paying close attention to what the median voter wants, to ensure the wanna-be fascists are defeated.

The authors at Loop Me In argue that popularism presents a kind of hollow “anti-politics.” But I’d argue that simply hand-waving about how the real thing to focus on is “movement building” is also a form of “anti-politics.” It ignores the fact that come 2024, regardless of the status of leftwing “movement building,” the Democratic party is going to have to take stances on issues, and which stances it takes will have at least some effect on who wins an extremely high stakes election.

What are we even arguing about?

One thing that’s confusing in these conversations is that there is no official definition of “popularism” over which to argue, only a variety of different arguments advanced by a loose collection of people on the internet. This results in a lot of arguments against strawmen, or against positions that people who associate with the “popularist” label don’t actually hold.

For example, the authors at Loop Me In claim that popularists “disdain extra-electoral activism and organizing designed to change public opinion and convince those with power to deliver on new policies.” But I’m a popularist, and I certainly don’t disdain these things. I have opinions on which forms of organizing and activism are likely to be most effective – “organized labor good, Sunrise bad” is a decent summary of my views – but I’m definitely not against organizing in general.

In general, I think long-term movement building and “popularism” actually go hand-in-hand. We have an acute, short term crisis, in the form of Donald Trump and the current iteration of the Republican party. In response to this, we ought to change our messaging to appeal to the median voter, in order to prevent downside risk. Separately, we live in a country with an electorate that is fairly conservative relative to peer nations in Europe, and we should try to change that over the coming years and decades by building up the leftwing movement.

These ideas don’t seem to me to be in tension. We should be able to walk and chew gum at the same time: the Democratic party apparatus should better optimize for winning elections, while the non-electoral parts of the left continue to try to effectively and durably move American public opinion.

This was a great article. I would just add- we could learn from the Republicans on this. They really want tax cuts for the rich, but they ALSO know this would be electorally unpopular. So what do they do? They are disciplined enough to make sure no one talks about tax cuts for the rich during the campaign (or at the very least make sure that any talk of tax cuts for the rich is embedded in a more broad based tax cut) - and then when they win power, they just go ahead and do it.

If there’s something you want to do that you know is unpopular, you don’t necessarily need to build a movement. If you’re willing to risk the potential backlash, all you need is the discipline to not talk about it during the campaign and then go ahead and implement it once you’ve won.

Great article Simon! I hadn't registered Coates's move to Marvel as especially strategic. That in conjunction with the point about cultural elites doing more to move opinion is fascinating. I am curious about the opportunities that presents for pushing democratic platforms through popular media. Is there a democratic belief, policy, or agenda item that you think Hollywood should focus on going forward that would be especially advantageous to moving public opinion? Also, is this an effort that is best done non-explicitly or, would it be preferrable to have producers and democratic comms/messaging experts help move the needle? I would also be curious about the short-comings or risks of attempting to compel voters through mass-media rather then from messaging that comes from the political apparatus directly.